“An ape, an animal-rights organization and a primatologist walk into federal court to sue for infringement of the monkey’s claimed copyright.”

No, this isn’t a setup for a joke made by the oddest person in the room at a cocktail party, or as they’re more commonly known, attorneys. This is the opening line of a motion to dismiss filed in federal court after PETA asserted a copyright infringement claim on behalf of an ape named Naruto. Here’s a look at PETA’s Copyright Infringement Claim.

PETA’s Copyright Infringement Claim Background:

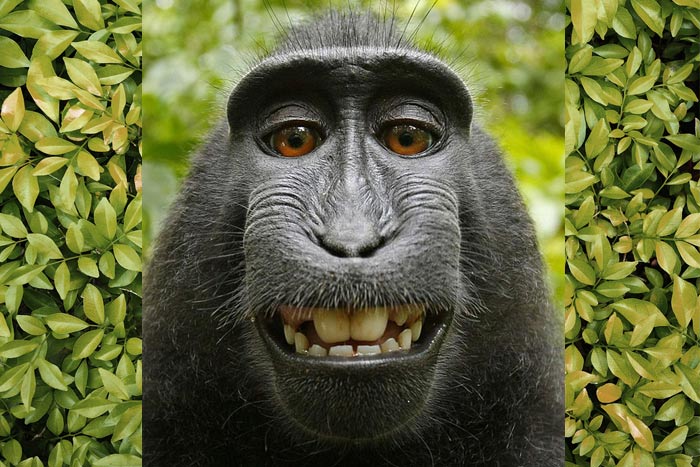

In 2011, David Slater, a British photographer, traveled to Indonesia to take pictures of the Crested Macaque, a black ape.

During his trip, one of the apes swiped one of Mr. Slater’s cameras and took a number of selfies, some of which were quite good. Despite Jane Goodall’s finding that primates are adept at utilizing tools, no selfie stick was used by Naruto.

Slater ended up fighting with the Wikimedia Foundation, which posted the monkey’s selfies online in its collection of public domain images. Slater said Wikimedia was violating his copyright by using the photograph. Wikimedia argued that Slater didn’t own the picture’s copyright, because he didn’t take the picture—the monkey did.

Copyright law:

Wikimedia relied on the U.S. Copyright Office’s opinion, contained in its Compendium II of Copyright Office Practices, Section 503.03(a) that “in order to be entitled to copyright registration, a work must be the product of human authorship”.

Copyright law only protects “the fruits of intellectual labor” that “are founded in the creative powers of the mind.” Trade-Mark Cases, 100 U.S. 82, 94 (1879). Because copyright law is limited to “original intellectual conceptions of the author,” no copyright claim can be asserted if a human being did not create the work. Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 58 (1884).[1]

Therefore, the monkey didn’t own the picture and, as Wikimedia asserted, neither did Slater, as the picture was not his authorship. Essentially, no one owned the copyright (though had Slater altered the photographs in a substantial fashion he would likely own the copyright of the changed photos).

Enter PETA:

In the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, PETA, on behalf of Naruto the ape, has now sued Slater for copyright infringement, arguing that U.S. copyright law doesn’t prohibit an animal from owning a copyright and that Naruto should be the rightful owner of his selfies. PETA seeks a court order allowing it to administer all proceeds from the photos for the benefit of Naruto and other Crested Macaques living in Indonesia.

While the U.S. Copyright Office explicitly stated that it only registers copyrights for works produced by human beings, Jeffrey Kerr, a lawyer with PETA, said the copyright office policy ‘is only an opinion,’ and the U.S. Copyright Act itself does not contain language limiting copyrights to humans. In fact, the Introduction to the Third Edition of the Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices admittedly states that “the policies and practices set forth in the Compendium do not in themselves have the force and effect of law”.

However, the U.S. Copyright Office goes on to state that its Compendium “does explain the legal rationale and determinations of the U.S. Copyright Office…….[and] the Supreme Court recognized that courts may consider the interpretations set forth in administrative manuals, policy statements, and similar materials “to the extent that those interpretations have ‘the power to persuade.’ Christensen v. Harris County, 529 U.S. 576, 587 (2000).”

Standing:

Standing is, simply put, the ability or right of a party to sue in court. The attorneys for Slater have moved to dismiss PETA’s case for lack of standing, arguing that a monkey doesn’t have the legal right to utilize the Court system to sue as an individual, even if a human or organization is serving as its representative.[2]

Realistically, PETA’s chances of having a Court grant an ape standing to pursue a copyright claim are slim to none.

Under Cetacean Community v. Bush, 386 F.3d 1169 (9th Cir. 2004), the test for whether animals have standing is quite simple: unless Congress has plainly stated that animals have the standing to sue, the Courts will not confer standing on animals.

Ostensibly, PETA’s case will be dismissed on that ground.

A change of opinion

Interestingly enough, in a recent local case, New York Supreme Court Justice Arthur Engoron, in addressing a dispute between a couple involving, among other things, ownership of their shared dog, changed his position on the legal status of pets.

After initially finding that “the parties each have the burden of proving why Stevie (the dog) would have ‘a better chance of living, prospering, loving and being loved’ in the care of one partner as opposed to the other” (somewhat akin to the factors used in determining a custody dispute over a child), he reversed his finding and concluded that: “‘animals do not have rights,’ and the correct law is the law of property, and this court will determine and award possession of Stevie according to that law, and no other.” Gellenbeck v. Whitton, 154365/2014, (Sup. Ct., NY County).

Justice Engoron, with apparent policy considerations in mind, went on to state that granting Stevie standing to have his interests considered “is unwieldy and unworkable, and would open up all manner of mischief.” Say, perhaps, the “mischief” of an ape being granted a copyright claim on a photograph.

While general awareness and a crackdown on animal mistreatment in both domestic settings and in the food industry has certainly increased in the past few years, (which most would argue is a positive development), it appears that animals have a long way to go before they can step paw in court to have their copyright claims rights enforced, both from a standing aspect and from a copyright aspect.

December 2015

Update (1/7/16): On Wednesday, January 6, 2016, a federal judge said Naruto who famously snapped a selfie cannot be declared the owner of the image’s copyright. At least, until Congress says otherwise. The Court held that there is “no indication” the Copyright Act extends to animals and punted the issue to Congress.

[1] This case actually involves Oscar Wilde posing for the plaintiff, and the use of the resulting photograph became the subject of litigation.

[2] Though standing for animals (via human representatives) has been permitted in regard to legislation specifically enacted to protect the animals in question (i.e. PETA can file a lawsuit against a zoo for mistreating its elephants and violating the Endangered Species Act).